Source: Figure B from Gerald Auten and David Splinter, Income Inequality In the United States

Americans and their elected representatives have long engaged in an enduring debate over income inequality and what the government should do about it. Over recent decades, they have turned their attention to the growth of income inequality, with the left decrying its deterioration and the right proclaiming that the inequality of total income and the consumption of households have not increased much, if at all.

The intensity of this debate belies its weakness as a way to resolve the tax and spending roles of government. The policy debate should focus on what the government should do to take advantage of opportunities, meet needs, and distribute the burdens of government fairly and efficiently. That’s true regardless of whether income inequality has grown.

Much confusion derives from sources of income unseen in many accounts, the problematic measurement of which sparks further debate. Market income and the type of income reported on tax returns understate the total income of poor, middle-class, and wealthy alike, though in different ways. When I reported that the average U.S. gross domestic income and product recently exceeded $200,000 per household, many were incredulous, as much of that income never shows up formally in their wages or bank accounts.

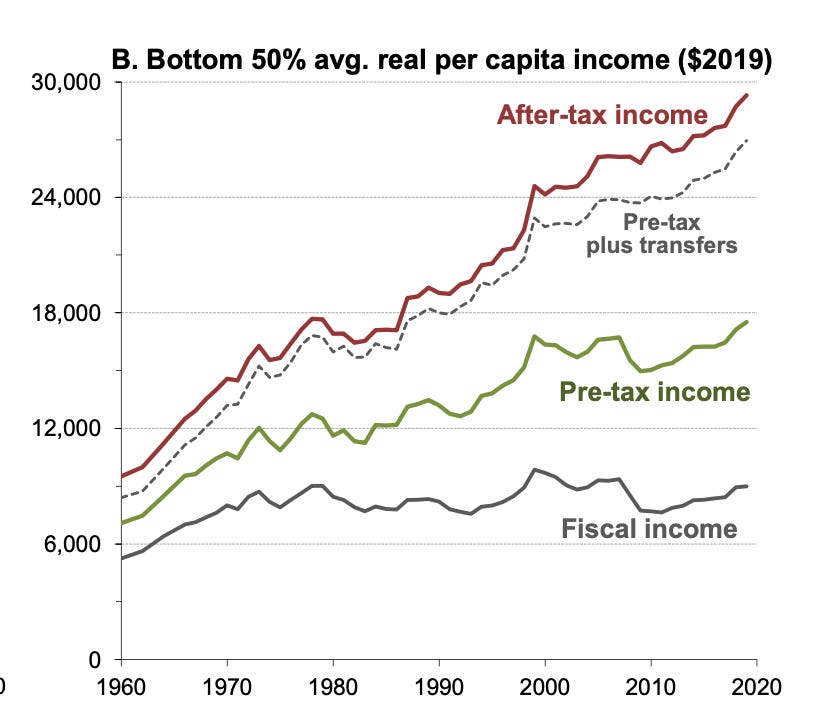

Drs. Gerald Auten and David Splinter recently re-engaged the debate over rising income inequality with one of the most comprehensive efforts to allocate all national income across different income classes. (Full disclosure: I provided some review of this research.) The graph above, from their paper, summarizes their measure of average income growth for all households with median or lower income.

The bottom line shows how the average fiscal income of Americans (essentially the income reported on tax returns) in the bottom half of the income distribution has grown little since the mid-1970s.

The higher lines next show how total income for these households has grown more substantially when one counts changes in employee benefits, taxes, transfers, and other unreported income. In their paper, Auten and Splinter also suggest that the top 1 percent of the income distribution has gained, at best, only modestly larger shares of total income.

In its lead opinion on January 7, 2024, the editorial staff at the Washington Post suggested that the Auten-Splinter research “has been received as a radical recasting of U.S. inequality." They also noted a substantial backlash and quoted Thomas Piketty, who said that “inequality denial” was like “climate denial." Auten and Splinter engage in no denial: they fully recognize income inequality and merely question the extent of its growth.

Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman produced some of the best-known studies on income inequality. But many other comprehensive studies, such as that by the Congressional Budget Office, and analyses, such as by Steven Rose, on productivity and middle-class income growth, use different vantage points and question simplistic conclusions.

Despite the intensity of the debate among researchers, their studies show many similar long-term trends and come to many similar conclusions. Wages and other market income have become much more unequal. Net government transfers, including Social Security, Medicare, and other healthcare supports (regardless of whether they appear on tax returns), have increased substantially—in fact, faster than economic growth. However, what is usually missed in the debate is that those losing out in the market are often not the same as those gaining from the net transfers. In particular, those transfers have only modestly helped working-class households achieve total income growth at the same rate as average households.

Even if the same people did get transfers that offset their market incomes, It is hard to believe that a continually rising wage and market income inequality is good for people, economic growth, and political cooperation. Among other reasons, the growth in inequality of market income—what people derive from their efforts to work and save—goes hand-in-hand with less upward mobility across generations for those born into poorer families. It also reflects increased inequality of the human capital and skills needed to thrive in a market economy.

A bit more detail. Almost all the growth in government transfers has come from Social Security and health care. That does a lot to increase the income—counting health care—of older, retired adults, but not the cash income and less so the total income of the working class. Meanwhile, employee benefits have also grown substantially, further dampening the cash wage growth of workers.

The unseen nature of many sources of income and the confused debate over the extent of inequality can dramatically affect government decision-making and the public’s perception of fairness.

Here are only two examples: Official and supplemental measures of the size of the poor population count cash benefits and sometimes child credits, but not health benefits, as income. Taxing the wealthy through individual income tax rates has limited effect as long as much of their income is derived from accrued, unmeasured, and untaxed capital gains. Those distinctions often distort our sense of the efficacy of transfers to the poor and taxes on the rich alike.

Pick the wrong measure, therefore, and you may misrepresent what has happened to the poor, the working class, and the wealthy—and what can be done about it.

In sum, despite the disagreement among researchers, they have improved our understanding of the distribution of the economy's income from all sources. That should allow us to move beyond the headline political debate to make more informed decisions about government policy.