Recent debates over who gets into Harvard and other prestigious colleges have focused on what factors admissions offices should or legally can use to admit students. Admissions processes discriminate along many lines—not just the contentious ones such as race and legacy preferences for children of alumni, but grades, extracurricular activity, geographical diversity, income, wealth, SAT scores, and whatever U.S. News deems as important for its rankings. Some forms of discrimination are considered acceptable, such as merit, ability, and need, even though they may compete with each other; some are not; and some remain grounds of contention.

Why do applicants to Harvard care? For many, it’s not about getting into Harvard. It’s about getting out. They want the discriminatory rules governing admissions to lean in their direction so that later they can benefit from the favorable but often unfair discrimination that society grants them as graduates.

To understand how this works, one needs to reflect on how statistical discrimination and tracking work in our society. Statistical discrimination, a theory pioneered by Kenneth Arrow and Edmund Phelps, occurs when members of a group are judged by some average group, rather than their own, characteristics. In an employment setting, for instance, suppose that all that is known individually about two candidates is that one is a Brahman and the other a Dalit (formerly known as “untouchable”), but Brahmans as a group on average have higher educational attainment. It is likely that the employer will hire the Brahman, a decision that Arrow argued was rational.

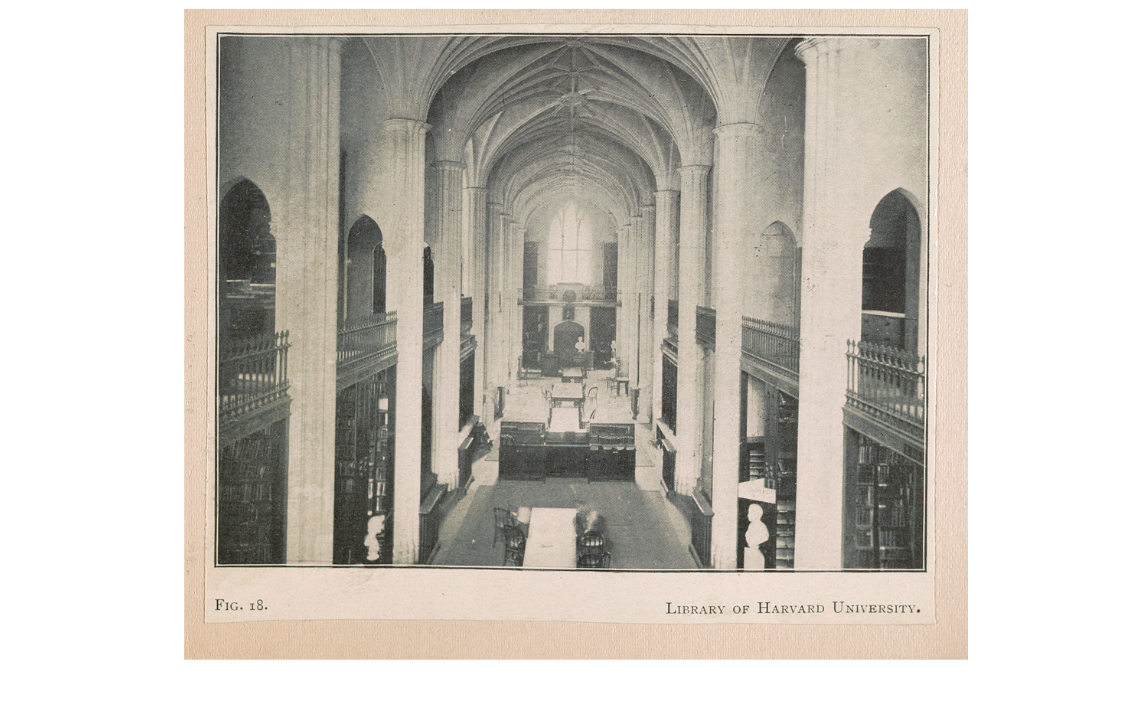

Society reinforces these trends. When renowned civil rights scholar and litigator, Charles J. Olgetree, Jr., recently died, the first attribute attributed to him in many headlines was “Harvard.” TV shows love to attribute a Harvard education to many of their characters as a way to convey automatically their above-average intelligence or distinction. (I’ve yet to see one show grant Dayton, my undergraduate alma mater, that iconographic mark.)

Our laws have outlawed some forms of statistical discrimination but not most. When outlawed, one complication arises when then trying to use the outlawed criteria as a correlate for something that some feel legitimately should be favored (sometimes labeled as “reverse discrimination”). That is, the issue arises not only in the Phelps case of discrimination against a disadvantaged group, but discrimination in favor of a disadvantaged group. For instance, the Supreme Court has lately decided that race can’t be used by those trying to discriminate positively to an individual from a disadvantaged race—in this case, to offset past negative discrimination against the group.

In Revisionist History: The Tortoise and the Hare, Malcolm Gladwell made note of an appearance by former Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia to American University law school. A law student there asked what it would take to become a Supreme Court clerk, the most prestigious of post-law school jobs. Scalia basically said, “Forget it.” He would not take the chance of picking someone from a lower caste law school. Harvard and Yale Law Schools had already done the winnowing for him. That’s an extreme but legal way of applying statistical discrimination to exclude vast portions of the legal profession.

In tracked systems, differences multiply. Following upon the work on relative age effects by Canadian psychologist Roger Barnsley, Malcolm Gladwell discussed in his book Outliers that Canadian children born early in the year were much more likely to become professional hockey players than those born later in the year. At the very early age in which Canadian kids start playing, the former group on average is more mature physically and mentally. That early advantage gives them more playing time and skill development that often adds to their relative advantage in the second year, and so on In the third and succeeding years.

The Supreme Court provides an extreme example of how tracking plays out along for years to come, with eight out of nine of the current justices having attended Yale or Harvard law school. Amy Coney Barrett was the rare modern exception, though she did come along another track for modern Republican appointments to the Court—association with the Federalist Society. The historical bias wasn’t quite so bad, with law schools like Texas and Berkeley having had one each in their history, compared to 22 for Harvard. Only three law schools have had more than three.

Tracking also takes place on a huge scale in the workplace. Staffing agencies look to the past records of potential employees, the assistant accountant who can move up to be head accountant, the vice-president in line to be president. In an initial winnowing of even whom the agency looks at, many people of the same or greater talent are excluded.

Somehow society has come to accept this type of discrimination in the employment world, but then it highly questions it when it comes to the academic one. With one major exception: sports. No one asks Alabama to compete against Auburn by giving all would-be football players an equal chance to play.

The difficulty, of course, is that ideally everyone should be given the opportunity to achieve to their maximum capability, no matter their current status. It doesn’t make sense, say, to hold back the 9th grade students ready for calculus, even if advantaged relative to other students by parental upbringing. Society, not just those individual students, usually gains if each person achieves maximum productivity. Certainly, a business organized around making profits and output for society inevitably tries to hire those best able to help them achieve those goals.

What to do? I can’t determine where a precise balance can be obtained, but I do suggest that all institutions should be organized around promoting maximum opportunity for all. Starting early can also make a big difference; it’s harder to play catch up or jump tracks as children age in school or adults age in their employment. I don’t believe in holding people back because that usually harms society as a whole. And I strongly support taxing the most successful, especially since much of their gain comes from advantages they did little or nothing to acquire, including being born in the right family, neighborhood, and time.

It's natural to want to help those we know. Parents promote their own children, friends their own friends, professors their own students. Old boy and, increasingly, old girl networks aren’t going to go away and, in some cases, can provide useful, though selective, information. But good hiring, admissions, and similar practices can develop more comprehensive and better information systems that try to minimize any inefficient and unfair disadvantages those networks impose on outsiders.

To me this is the much bigger and tougher discrimination issue largely ignored in the Harvard debate. It’s not just a matter of equity. It plays a big role in the increasing divisions in our society and politics, where many feel left out.

Another piece I need to write but am trying to put into a forthcoming book. Putting more debt on students only makes sense if the net effect is to increase their new worth...sorta like a well-functioning mortgage increasing net equity in a home over time. In fact, what has happened over the past few decades is that student debt has displaced other subsidies such as for public education, so the net worth of the young, adding together human capital, which really hasn't gone up much, if at all, with net financial capital, which has gone down substantially.

Too many issues to cover in a short piece. Most of us recognize the extent to which we feel we have lost out due to some unfair discrimination but give less attention to when we have been favored.