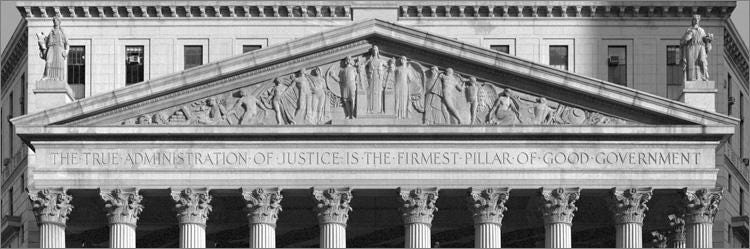

New York County Courthouse

Words serve as metaphors that can never fully capture an ever-evolving reality. In fact, we can’t even perceive three-dimensional objects in more than two dimensions. When someone uses words, therefore, we must delve deeper and navigate around, above, and below the object or term to grasp what that person is trying to communicate. In the political realm, words can be particularly contentious, as political debates revolve mainly around gaining or maintaining power.

Recent powerful actions have been justified with the words “free markets” and “equity.” Jeff Bezos has informed the editors and writers of his Washington Post Opinion page—and, indirectly, the Post’s readers—that he will dismiss those unwilling to emphasize “free markets and liberty.” President Trump and his DOGE followers terminate individuals identified, sometimes through algorithms applied to government data files, as having discussed or promoted “equity.” Both Bezos and the President use concise language to define and deem individuals as unworthy of employment and to silence discussions regarded as unacceptable to the Post and government. The cancel culture typically associated with the left on college campuses has now been appropriated by the right to establish its own set of speech codes and safe spaces.

At the risk of offending many on the left and right in the media, think tanks, and government who have long abused these words, I’m going to try to explain what these words mean in different contexts. As may be obvious, the concepts “free” and “liberty” relate closely to “equity.”

“Equity” or “fairness” usually implies one of three principles: equal justice (or equal treatment of equals, or horizontal equity), progressivity (or vertical equity), and liberty (or individual equity). The first applies almost universally, while the latter two often legitimately conflict. Both progressivity and liberty can align with or conflict with another principle: efficiency. In what follows, I outline these four principles and suggest that productive actions require carefully employing these words.

Equal justice (or equal treatment of equals or horizontal equity)

This idea of equal treatment of equals traces back at least to Aristotle. I call it the queen of principles because, like the queen on a chessboard, it wields influence in nearly every debate. Almost everyone, even the most unjust person, acknowledges at some level that equals should be treated equally. The phrase “equal justice for all” fundamentally emphasizes equal treatment under the law.

This principle justifies the promotion of racial equity, as seen in the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution and various Civil Rights Acts. If the only difference between two individuals is the color of their skin, there is no valid reason to discriminate between them. Naturally, when considering any two real individuals, rather than just abstract ones, they will differ in many ways. A weaker version of this principle would claim a mistreated person’s right to seek equal treatment from peers. This, however, requires that person to provide evidence of being a peer. A stronger version of this principle asserts that the discriminator instead bears the burden of proof for their discriminatory actions.

Now, before you start thinking you don’t discriminate, consider your actions. You form friendships with only certain people, you join specific clubs, you support some relatives more than others, you prefer certain sellers over others, and so on. The issue isn’t whether you discriminate; it’s whether you have a reasonable, often practical, and least harmful-to-others basis for that discrimination.

Even in the most contentious political debates, both sides usually appeal to this principle. Those making outrageous arguments for vengeance or for arbitrarily attacking Black individuals, immigrants, or civil servants justify those actions by “othering” them, rendering them unequal and unworthy of equal treatment. As C.S. Lewis so eloquently explains in Mere Christianity, our consciences demand that we justify our actions, even when we lack empathy for those we intentionally hurt. Abusers will argue that their actions are merely fair or tit-for-tat.

Progressivity (or vertical equity)

Progressivity is based on the idea that those with greater means and lesser needs should support those with fewer means and greater needs. Despite claims to the contrary, I assert that almost everyone implicitly accepts this principle at some level. My proof: parents contribute more to the family’s income than their children do; people with income pay more taxes than those without. The legitimate debate centers on how much progressivity and how much power of the state should be used to promote it.

As societies grew wealthier, they established programs that directly benefited individuals, including Social Security, healthcare, and welfare. While they had long subsidized education and transportation to improve a nation’s efficiency and long-term growth, they increasingly shifted towards transfer policies in the 20th century for benevolent or progressive reasons, such as reducing poverty in old age.

Liberty (or individual equity)

Liberty entails individual rights to act as they best see fit, whether regarding religion, work, or other practices. John Locke argued that individuals have a natural right to the fruits of their labor, and when that also entailed using natural resources, to property ownership of those resources. Religious doctrine also promotes the right to the fruits of one’s own labor. This concept is often applied by workers to their rights vis-à-vis employers and by libertarians and taxpayers to their rights vis-à-vis the state.

Efficiency

Efficiency fundamentally involves maximizing benefits relative to costs. However, many of the associated benefits and costs of an action, along with the non-financial impacts on different individuals, cannot be accurately quantified. Therefore, we utilize alternative strategies to achieve efficiency, including fostering competition among businesses, evaluating cost-effectiveness, and enabling democratic processes to decide which public goods to acquire.

Harmony and conflict among principles

Equal justice coexists harmoniously with other principles, with the notable exception that enforcement costs restrict how far it can be applied. Even in special interest legislation that contradicts this principle, such as favoring a specific crop to secure farm votes, the law typically still mandates that equal rules apply to those who qualify (e.g., those cultivating the favored crop).

Progressive practices can conflict with liberty and efficiency, yet they are typically most effective when aimed at fostering horizontal equity. For instance, our Social Security system helps reduce poverty by taxing single individuals to fund survivors’ benefits that they cannot receive. This approach would deemed inequitable and illegal with private retirement accounts because it provides unequal justice. But it is also an inefficient strategy for alleviating poverty or helping widows.

Efficiency often aligns with individual equity. Adam Smith argued that if two parties can benefit from an exchange, the government should allow them the freedom to do so. Of course, there is one major exception: when the transaction restricts the freedom of a third party.

Even so, competition among individuals striving for their own goals in a society that values individual liberty can help foster an economically richer and more dynamic community. American society strongly encourages an entrepreneurial spirit, and even countries like China have recognized how competing private businesses can drive economic growth.

Regardless, all government actions, whether aimed at promoting progressivity, defense, or commerce and growth, necessitate regulation and taxation that restrict individuals' liberties.

These tensions—and I have only touched upon some—require balancing, not discarding, the underlying principles. For any degree of progressivity, for instance, the policy should promote equal justice among equals and efficiently promote the goal. Similarly, the U.S. Constitution largely allows majorities to determine the proper balance between progressivity and liberty, but it prevents majorities from overriding stated individual liberties and specifies some types of discrimination as unlawful.

Application to today

So, what does all of this mean for current debates?

For one, using the term “equity” doesn’t help us determine what kind of equity is being addressed. DEI programs often failed to specify what “equity” meant in practice. However, the criticism of DEI itself hinges on the idea that it can lead to inequitable practices, such as unfair reverse discrimination. If government leaders foolishly want to dismiss anyone discussing equity, then they must let go of anti-DEI and DEI promoters alike.

Regarding “free markets,” The Economist magazine takes a balanced approach to analyzing public issues while promoting free trade, individual freedom, classical liberal values, and fact-based analysis. I can’t assess how Bezos thinks the Washington Post differs and has failed to achieve balance. I primarily access the Post for its unique efforts to hold all U.S. government officials accountable. Will that continue?

In sum, our failure as a society to address numerous problems arises when we loosely apply a few words, catchphrases, and labels to rationalize our actions and treatment of others. No terms are more powerful, yet misused, than “equity,” “free,” and “liberty.” When used carefully, they offer valuable insights on how to build a better society. In our current cancel culture, both the left and right increasingly wield them to silence and dismiss others.